In the last section we wove our way around the Barrier Islands in the fog, headed out into the open water, around the next point and anchored in Queen Cove. Our guide book had hyped up Queen Cove, so we were quite disappointed to find houses all around and clear-cuts. Another large sailboat came and anchored near us, but the wind was blowing hard so all of us just stayed hunkered below. We found out from other boaters later that this sailboat from Seattle, had been there two weeks just puttering around and anchoring there each night. It was beyond us why they picked Queen Cove as a base camp.

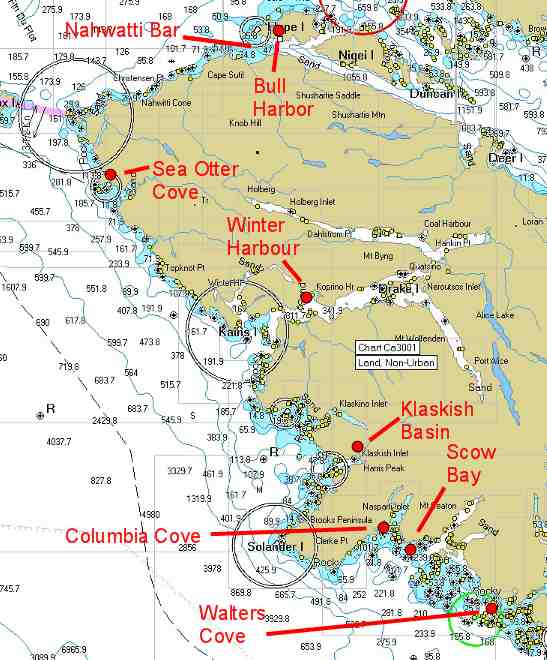

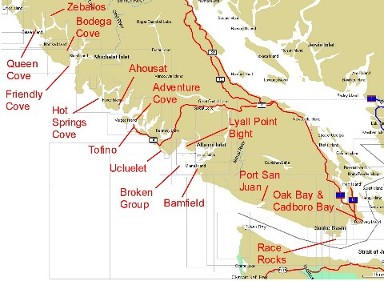

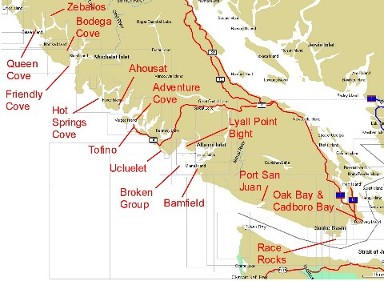

The southwestern portion of Vancouver Island is very large, and we wanted to see as much as possible. Spending two weeks in one place just didn't sound like fun. In fact here's an overview of all the spots we hit along the way.

So with so many places to go, we left this sailboat to enjoy the clear-cuts, and headed up an inlet to the small town of Zeballos. We were promised restaurants, fuel, water, and a "well stocked store."

APPROACHING ZEBALLOS

APPROACHING ZEBALLOS

Fortunately for the authors of our guidebook, Zeballos lived up to their promise. We were able to get fuel, water, do three loads of laundry and even topped up our propane tank. The best part was of course having a rare dinner out. We checked out all four (yes a glorious four choices!) restaurants before going with the one with the vegetarian chef. He even came out of the kitchen, shouting, "Ok, so whose the vegetarian out here?!" He fixed us a special entree and commented that it's tough out here because everyone eats meat. He was quite impressed to learn we were both vegan.

After a great dinner, we learned that there was dial-up internet access at the library (open Tues/Thurs. 3pm to 5pm). Since it was Wednesday, we were tempted to skip it because we didn't want to pay for another day at the dock. After consulting our charts, we decided that we could leave at about 5pm the next day and still make it to the next anchorage before dark.

We waited outside the library like nerdy school kids for the librarian to open the doors. I was armed with two long stories to email out on CD and on a USB mini-drive (thanks to Wayne who gave me one!). Their ancient computer couldn't read any of these, and our internet plans went bust. On the plus side, Sherrell did manage to pay a bill before getting a late fee, and we shot off a few short emails to our parents so they wouldn't worry.

The downside of waiting so late in the day to depart, because we're too cheap to pay for another day at the dock, meant trying to get to the next anchorage before dark. Traveling these log-filled fjords in the dark can be a risky business.

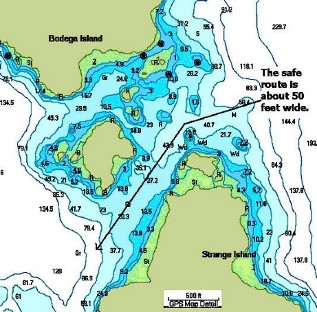

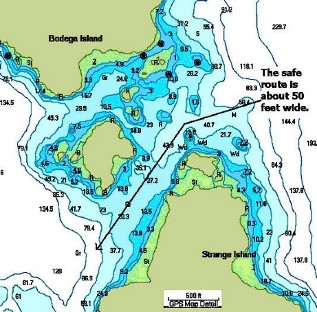

Our goal was a small cove north of Bodega Island. The cove is a land-locked little basin that is really well protected, but with the strong head-winds, adverse current and the setting sun against us it seemed dicey getting there. As a backup, there was a smaller cove in very deep water, which we would have to set two anchors to keep from swinging into the deep water. After a long evening of trying to get through the fjords, we took a look at the deep water cove, and decided to press on to a better anchorage. The impending darkness encouraged us to take a short cut through Princessa Passage; a short, but narrow, shallow and rock filled section that would cut an hour off the trip.

The current through here sometimes rips along, and it's easy to get set against the rocks. Gripping the tiller while Sherrell kept lookout on the bow, we floored it through there to limit the amount of drift caused by the current. With the rocks and islands in such close quarters, traveling next to them at 6+ knots can really feel like a slalom ride. We weaved past the rocks and dodged the outcrops on the islands in a matter of seconds, but when you're unable to breathe, it seems like minutes.

Once we caught our breath and turned up into Bodega Cove, we felt vindicated for going the extra distance. There were lots of birds--we could almost reach out and touch a large eagle when we came through the entrance. And there was a large tidal flat that was cool for hiking.

We landed our dinghy on a beautiful grassy meadow (prime bear real-estate). Hiking through the area revealed a small stream and some pretty fresh bear scat. Since we had heard that bears are sometimes sighted here, I let Sherrell lead the way.

We spent an extra day at this anchorage, just to relax and hopefully catch sight of a black bear. Since you only see the photo of "Bear-Bait" Sherrell, you can guess we didn't spot any.

From here we motored down to "Friendly Cove". This was the historic site where in 1778 Captain James Cook "found" Nootka Sound and repaired his vessel with the help of friendly natives, thus the name of the cove. Well, Spain had claimed sovereignty over the Pacific Ocean since 1494 and when they sent someone to whoop up on the other Europeans who started trading Sea Otter pelts, they were pissed. In 1789 Don Estevan Martinez from Spain arrived and took possession of the port and the "foreign" vessels, which were commercial vessels. After some political hustle and tussle, they worked out the "Nootka Conventions" in Friendly Cove. This laid the groundwork for laws that still stand today regarding foreign flagged commercial boats, which allow them the freedom to move about the seas, despite the current political environment of their homelands.

The story takes a more interesting twist when Chief Maquinna, whom had witnessed all this nonsense, moved out of the area to avoid the conflict between Spain and England. But in 1803, another ship out of Boston arrived in a nearby cove hoping to make a fortune on Sea Otter skins like the ships before him. The Chief, however, had learned their true value, and knew he had been getting ripped off for years. He greeted the ship and John Slater warmly as usual. John Slater gave him a gun for shooting foul, and the Chief returned with several ducks for him and showed him one of the gun's locks had broken. John took this as a gesture of contempt and belittled him with a long string of salty sailor swearing.

Well, that night, the Chief and the elders hatched a plan. They got Slater to send 9 men ashore and in a surprise ambush, they killed them in bloody hand to hand combat. They then proceeded to kill 24 of the 26 men on the boat, leaving the metallurgist (for his skills) and a man found hiding later to serve as slaves.

Chief Maquinna's tribe was now the only one equipped with an armed sailing vessel. They took the cargo and moved the ship to Friendly Cove, where they burned it to the waterline. The white slaves were eventually freed, and they had the wisdom to encourage the English not to punish Chief Maquinna as it would fuel an endless cycle of violence.

The bay isn't very large. It is also open to the ocean, so some swell from the Pacific enters, but despite all this we had to check this place out. We weren't the only ones to feel like strangers on these old shores. In fact, in 1788 John Meares dumped two Chinese carpenters off in Friendly Cove and told them to build a ship. He returned to find the ship completed, and in Sept. 20, 1788 a schooner was named "Northwest America" and was the first ship ever built on the West Coast. Imagine being dumped on a remote foreign land and being told to build a ship with only the tools you have on you...sheesh.

Anyway the weather was calm and the anchorage wasn't too crowded when the tour boat wasn't around. (This photo is taken from the Coast Guard Lighthouse).

Our boat is anchored in the middle, just off the bow of this large local tour boat that is backing away from the wharf.

This was once a thriving native village, but only one native family lives here full time now, as caretakers. The rest moved onto a reservation next to a white town to work at the lumber mill. Back when this was a thriving village, the natives built a pretty little church, after being converted to Catholicism by the Spanish. Several years ago, the elders decided it was time the tribe got back to their native roots, and replaced the altar with these beautiful totems. Now, it's really dedicated to their beliefs, rather than Christian dogma.

The totems are family totems with the various spirits that signify importance in their family.

The back of the chapel was even cooler.

During ceremonies they can lower the Thunderbird down to pickup the Orca (the dark black spot on the floor to the left). The Thunderbird lifts the Orca up and then spits oil out of it's beak onto a fire. Its an old tale about the beginning of the universe. And I'm sure it's spectacular to watch, especially with the Thunderbird spitting fire in the middle of church!

From the church we hiked down to the pebble beach and explored some of the amazing rock formations.

Can you see Sherrell in there? We hiked for miles along the shore and through the reservation checking out all the critters.

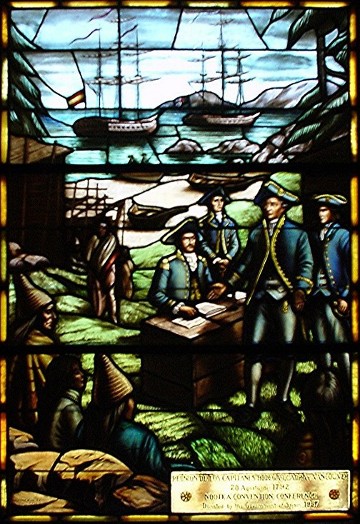

Before we left I had to take a look at the stained glass window donated by the government of Spain to this tiny little band. The glass depicts the negotiation of the Nootka Conventions between Spain and England. I noticed a distinct LACK of recognition from England. Perhaps they're still pissed about their boat and the tragic loss of their countrymen. (Notice in the glass that was given to the natives mind you, how the natives are sort of off to the side and incidental? Also notice that the Spanish ship is closer and more prominent than the English ship?)

We sat aboard Sarana thinking about how much history happened here and how very little the First Nation People got out of the deal. The total land given to this tribe by Canada was about 600 hectares (1483 acres). A sliver of an area of where they used to be free to roam. Almost 75% of what Canada took is being clear-cut or is planned to be cut. This includes many old-growth strands of trees that are centuries old. In fact, the nearby Nootka Island is almost a total wasteland of clear-cuts. Such a sad legacy. And to think, archeologists have proven there has been native settlements in this area continuously for over 4,300 years! And now they barely have a pot to piss in.

We slipped quietly and somberly out of the harbor in the morning and sailed to a spot we hoped would ease our bodies as well as our souls: Hot Springs Cove.

As we rounded Estevan Point (remember Captain Don Estevan Martinez from earlier?) we shot a picture of another historic site: Estevan Point Lighthouse. It was poured almost continuously and holds the dubious honor of being the only place in Canada ever under attack by a foreign country. Can you believe it? I guess during WWII a Japanese sub took a pot shot at the light house and tried to tear it down. Obviously they missed.

We were able to sail almost all the way into Hot Springs Cove. We were so excited about soaking our tired bodies in the hot sulfur water. Little did I know that this place would be proof that there is a Heaven. Heaven, it turned out was hidden here all along!

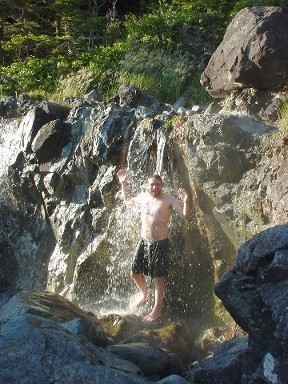

This steaming hot waterfall is pumped out of the Earth from over 5km below. It's heated to 104° Celsius (hotter than boiling for you standard folks) and is cooled to about 50°C (about 130° F, I guess) when it exits the Earth's crust.

I was beside myself in disbelief. Who could have ever imagined something so amazing here in the wilderness? A hot natural shower powered by a 5km underground natural pump. Magic isn't it?

This waterfall fell into several pools which were progressively cooler. My favorite was right there at the top. I laid down in the pool and let the waterfall just pour over me. The deep pump in the Earth would irregularly speed up and slow down the water kneading my tired muscles. I felt like the water was under control of some unseen spirit, gently searching for all the sore spots.

I laid there in bliss with my body immersed in the water with only my eyes and nose poking out. The sweet rumble of the water and it's random massaging hot water was wonderful. And before you think I've lost it, you're not the only one. I encouraged Sherrell to try my spot of Heaven and as her face was sprayed by the steaming water she sat up quickly and said, "That sucks its going up my nose." Perhaps my heaven isn't for everyone.

Sherrell did enjoy the steamy shower, though.

And the trail to get to the Hot Springs is a 2km long trek along a nice boardwalk through old growth trees. Some of them were massive! We guessed they had to be 400 to 500 years old!

After spending two days soaking in the hot springs, we started heading towards a bay near a Native Reservation called Ahousat. Leaving Hot Springs Cove, we felt refreshed and ready for more travel. As we exited the cove and turned up the channel, Sherrell was raring to go and suggested we hoist our spinnaker.

We bought the slightly used spinnaker in Seattle and hadn't had a chance yet to see how it fit our boat. Well, actually we tried to pull it up to the top of the mast once in very light wind while at the dock on Lake Union, but it quickly filled and just about pulled us onto the boat next to us. So, I quickly announced that the spinnaker would fit, and doused it like a madman. The truth is we didn't know if it would fit, or if it was even the right type of spinnaker (asymmetric), but at $150 bucks and with it in great shape, we chanced it.

Sherrell said now was the time to test it out -- light wind, flat seas. So I set to rigging everything up (also for the first time on our boat). I walked Sherrell through the basics of handling the spinnaker, and then promptly hoisted it into the sky. It quickly filled with air, and I realized to my chagrin that it was sideways. A little flustered, I doused it, rotated it (marked it for future reference) and hoisted it again.

It went up cleanly and opened to reveal its black, yellow, orange, red and white glory, or should I say gory. At any rate, the big bright sale filled magically and started pulling us through the water at 3-4 knots.

Unfortunately it turned out to be a symmetrical spinnaker, and a little too small for our boat. However, with some creative trimming, I was able to make it fly nicely as a pseudo-asymmetric. For the price, we'll take it!

Sherrell really enjoyed the spinnaker once we got it up and going the right way. I talked some more about some of the things that usually go wrong with them and what to look for as the wind gradually built. To avoid having any of those bad things we were discussing come true, we doused the spinnaker in what turned out to be minutes before the wind really started blowing. Trying to take down a big sail like that in a lot of wind (in a narrow channel, nonetheless) can be an ugly scene.

We sailed on with just the genoa and worked our way around to the little bay by Ahousat. The bay borders a marine park and the Native Reservation. We went to shore and hiked several miles through DEEP mud bogs. These mud bogs were the type that suck you down and don't let go. They're the type of bog that makes those wet slurping sounds as you struggle to pull your boots (knee high boots) out of them before the mud oozes inside.

Slipping and slogging our way through the trees we emerged onto a powdery sand beach. The soft powdery sand was a dramatic change from the sucky-mud. We walked along the shores and found another path that had recently been made, but this time most of the trail was a boardwalk. Having left our boots behind in the sand, we decided to attempt it barefoot. We "oohed" and "ouched" for about a half a mile until we emerged onto another beach. This beach lead to the "Trail of Tears" built by the Ahousat natives. This trail is a 15km march to Cow Bay (where grey whales often feed). Lacking shoes, the trail of tears sounded a little too much for us, so we turned back for the boat.

The next day we headed out for Tofino, one of the largest towns we've visited. Tofino is a major tourist destination for land-locked Canadians. They were here for the long weekend (Canada Day) and they packed the town. Even the marina was full and we had to reluctantly raft with a surly sailor in his big blue boat.

Tofino also turned out to be a Mecca for surfers. There were posters of surfers riding the tubes and doing tricks on the icy water on the west side of the peninsula. Tofino sported a strong counter-culture of surf bums. The local monthly newsletter even featured a surfing trick of the month, executed nicely by one of the local surfing experts.

Several residents didn't seem to appreciate this invasion. The middle class method of protest, the bumper sticker, promptly declared: "Hippies Suck".

Despite all of Tofino's tourists, we were able to restock and get underway quickly to go to another historic site in a bay known as Adventure Cove. This bay was where the first boat to circumnavigate the world with the United States Flag was built. It sounded like a good spot to check out.

Captain Grey built a 45 ton sloop and sailed it around the world. I was surprised to learn that the first American to sail around the world built his boat in an obscure cove in Canada.

What we found in Adventure Cove turned out to be much more interesting than an old archeological site. We found a big black bear!

He was there for several hours in the evening and the morning just eating different grasses and rooting around in the low tide line. He was patiently combing the shore for snacks and was fun to watch. Since he was busy at the archeological site, we let him enjoy it alone. Captain Grey will have to wait for another day.

Early in the morning "Barry" was up and looking for more snacks. Since we decided to head to the next stop, Ucluelet, before the tide changed, we raised the anchor and got underway. All the while, Barry didn't even notice us and all the noise we were making.

For the third time, we wound our way through the rocks and shallows (about 10 to 20 feet of depth under the boat most of the way) with shoals on all sides, towards Tofino. Nearing Tofino, we turned south and headed back into the ocean for a 16 mile leg offshore.

The wind had picked up and was blowing directly at us, so we were unable to sail. As we moved further offshore, the boat started to slow to a crawl. We were over 3 miles offshore in the middle of the open water, but suddenly there was 3 knots of current against us. We were barely making 2 knots and the short 16nm leg was looking like an 8 hour slog.

After battling the current for a couple hours, and searching all of our sailing references for some mention of this phenomenon, we opted for hot showers and doing a load of laundry back in Tofino. We turned around, put the sails up, and did a brisk 8 knot sail back to Tofino in less than an hour.

To save money, we tied up to the very busy, but free, public pier and went in search of someone who might know about the currents, so the next day we wouldn't waste our time fighting it.

We found a cool fisherman who agreed it can be a slog out there heading Southeast, as the prevailing current generally sets Northwest. We speculated it had to do with the Straits of Juan de Fuca dumping into the ocean. He was a pleasant guy who had traveled to many of the same places in Asia that we did in the early '70's. We exchanged stories of Singapore and how dramatically it has changed since the '70's when it was a fledgling 3rd world country. He was surprised to hear of how it's a strong 1st world country with all the modern conveniences to rival Tokyo.

Parting ways, he wished us luck, and we went off to do laundry and take showers. Upon returning to the busy public dock, we found several friendly and tipsy Ahousat natives hanging out on the pier. When they saw us climb aboard our sailboat, the whole group lit up with excitement.

Realizing we were the ones on the sailboat, brought a flurry of questions. How big is it? Where did you come from? Did you name it? What does SARANA mean? After being alone most of the trip without a lot of people around us, we felt overwhelmed by the crowd and tried to answer their questions as rapidly as we could.

There was one pregnant woman there who liked the boat name so much, she decided on the spot that if she had a daughter, she would name her Sarana. She made us write down the information for her and we helped her pronounce it several times. The group was waiting for their local watertaxi to give them a ride back to Ahousat, where a 5 day sports festival was underway. They practically demanded we go with them.

After debating it for some time, we decided that backtracking that far would really slow us down for another 4 days. Other members of the Ahousat band came by later that day and invited us over for the festival too, it was a bummer it was so far out of our way. Too bad we didn't know about the party several days ago when we were there. Sadly, we had to press on.

To beat the tides we departed at 5:30am, but not before the last Ahousat could say goodbye. At about 3am, there was a knock-knock-knock on the hull. I stuck my head out to see one of the guys we had met earlier holding up 2 beer bottles as an invitation to join him.

We laughed and I apologized that I couldn't join him. We were departing early and I was dead tired. When 5:30am rolled around, we quietly left the pier where his slumped form was sleeping in the morning dew. Sometimes it is easy to understand why some of the reservations choose to go dry.

Leaving Tofino, again, we had much better luck. With a slight wind from behind us, we flew down the coast at over 5 knots. An amazing change from the grueling crawl the day before.

Rounding the lighthouse 16nm later, we approached Ucluelet, the town on the west side of Barkley Sound. Only 30 minutes by car from Tofino, Ucluelet was much quieter and was surrounded by hiking trails.

We hiked about 15 km along the rugged coastline we had just traversed by boat.

We left the main trail and bushwhacked some along the shoreline, until we ran into a rather tame white-tailed deer.

This little guy became our local tour guide and led us through several animal trails for about 15 minutes, until deciding the pay wasn't good enough and ducked off the trails to wait for us to pass on our own.

The hiking was great, we really wore ourselves out. We collapsed in the cockpit of the boat, and then grilled up some delicious Portobello mushrooms that we scored in one of the stores.

The next morning we set off in the wispy fog for Lyall Point Cove where lots of puffins have been sighted. While winding our way through the reefs, a large Gray Whale surfaced 10 feet from our boat! Sherrell thought we were goners, but I grabbed the camera and waited impatiently for it to power on.

I slammed the boat into neutral and while I was searching the water for the whale, I realized the stupid camera still hadn't turned on. I gave it a good shake, just to show it who was boss as I spotted the whale under the surface of the water. He had turned the other direction and was on his side looking up at us from under the water. I could see his large eye looking at us from his watery home.

Just then he turned over and lifted his spout out of the water and blew a 15 foot high plume of water into the air. The damn camera still wasn't ready to take a photo. As he started to slip back below the water, the camera finally was ready for action, almost a second too late I snapped his picture.

As he sunk below the surface, an obnoxious smell overtook us, like rotting fish and seaweed. Sherrell and I made faces at each other and said at the same time, "Whale breath!"

We hung out there for a little while longer to see if the beastie would come back, but he seemed to have gotten an eyeful of us and dove deep.

Sherrell's adrenaline rush lasted the last 8nm to Lyall Point Bight. This is a small indent into Vancouver Island. The anchorage is exposed to the west and northwest, but our guide book proudly declared there were lots of seabirds in this area, including the colorful tufted puffin!

A good 20 hours into watching for puffins, we spotted an amazing zero. In fact, there were no sea birds whatsoever, not even a seagull! Stupid guide book.

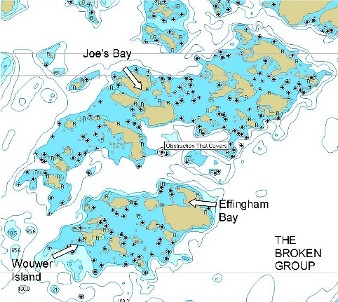

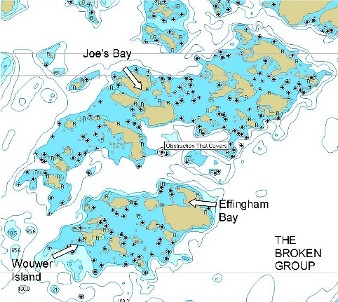

Fine then! Onward to the Broken Group! They have a funny name, but if you were to see them on the chart, it would make sense. The Broken Group is a pile of islands, rocks and reefs in the middle of Barkley Sound. They cover an area less than the size of the San Juan Islands in Washington (about 15 miles by 15 miles), but there must be about 200 or more islands. Hundreds of kayakers come here every summer to paddle in and out of all the rocks and islands. This is paradise free of clear-cuts. The Broken Group is fully protected as a Marine Park by Canada, thank God, because nothing seems to be safe from the saw out here. It's a good thing our mast is metal....

We decided to start our introduction to the Broken Group by anchoring in Joe's Bay, which is large bay formed by a ring of 5 islands. On the chart it looked protected in all directions, even though it's a stone's throw from the Pacific. Gale winds from the northwest were forecast for the next two days, so it seemed like a good place to hide.

Since this was the first gale for the southern half of the island for the last two months, we were a little skeptical, but we didn't take any chances. And neither did the other 11 boats that shared the anchorage with us. This is the first time where we've been in an anchorage and had more than 3 or 4 boats. It was strange, but we sort of expected more crowds. This area is easily accessible to American and Canadian boats from Victoria and Seattle. Almost our entire time in the Broken Group, we saw nothing but American yacht after American yacht.

We tried to pick a spot out of the wind and away from the other boats so we would have room to swing around on the anchor. After about 2 hours, the wind had built to about 30 knots and the boat next to us started to drag anchor. They started dragging towards a rocky reef, but they were quick to recognize the problem, and pulled their anchor up and moved to a new spot.

Another 2 hours passed and the gusts had increased in strength. And for the first time since we've had the boat (7 years), we started to drag. It was a little surprising because we have a very large anchor, and all chain rode. We quickly pulled up the anchor and headed for a spot with fewer gusts. As we dropped the anchor, we came to the realization that there was some kind of misunderstanding between us about the depth. I hadn't put out enough chain the first time, but this time we put out plenty and stayed put throughout the rough wind storm. But the boat that drug earlier, drug again and had to reset their anchor. We found out the next day, they were up every hour all night checking their position to make sure they hadn't drug for the third time.

Eventually the wind calmed down enough for us to explore the surrounding islands some, and we discovered a huge oyster bed. They were big too. The small ones were about 6 inches and the big ones were almost a foot.

There were hundreds of thousands of them. The water was strangely warmer here than in most areas, and it encouraged a lot of sea life to grow, like this bright blue star fish, who matches the blue jacket I seem to always be wearing.

After the roughness of the gale had left us, we ventured to the outer edge of the Broken Group. We went to Wouwer Island, where it is very difficult to anchor. The only protected spot we could find was a narrow spot inside a little cove with underwater rocks and reefs on either side, and we had to tie the stern to the shore, because there wasn't enough room for the boat to swing around.

You can't see the line in the photo, but there is a continuous line running from our stern around a tree on the shore and back to the boat, about 300 feet long in total. The difficulty in anchoring here makes this island rarely visited, especially since it is the furthest out into the open Pacific. It was full of virgin old growth forest.

Even the Eagles were not bothered by our presence.

We hiked across the island through the underbrush to the exposed Pacific side. There were no trails and we had to push our way through the brush. Exhausted and covered with twigs, moss, and lots of rotten wood bits, we emerged on the other side to a view of the rocky reefs and the Pacific. There was supposed to be a beach here, and somewhere in the dark green forest we must have lost our bearings and missed it.

We tried to skirt the rocky cliffs and work our way south to the beach, but we were quickly up against large cliffs, so we pushed way back into the thick forest. After about 20 minutes of fumbling around and not finding the beach, we crossed the island again to return to the boat. Climbing hills, stumps, scrambling over brush and skirting cliffs we managed to make it back to the other shore. Only we were cut off from the water by a large cliff. Drenched in sweat, we reentered the forest and tried to work our way around the large dark cliff wall, until we were up on top of it looking down onto the water.

Performing the classic, "sit and slide" technique, we slid down the steep muddy, mossy embankment to the water line. From there we were able to work our way back to our starting point and the dinghy. Sherrell was picking twigs out of my hair and commenting on how the island probably has a few new confusing trails for people to follow.

After recovering from our three hour tour, Sherrell rowed us back to the boat where we collapsed and planned our next stop, Effingham Bay.

Effingham Bay is a somewhat protected anchorage, but what got me excited was the big sea cave on the far side of the island that you can hike to. So the next day we found ourselves anchored in Effingham and deep inside another old growth forest. Aren't these places spectacular?!

How could ANYONE even think of cutting down these places for cheap timber? It boggles the mind. We hiked deep into the forest to cross the island. Along the way we ran into a large fern meadow, like something from "The Land of the Lost."

Hiking down the beach and scrambling over rocks, we searched for the sea cave. We heard you can only get into it at low tide, and the tide was rising fast. After about 1/2 mile of scurrying over rocks, we found it!

Here I am imitating a certain blue starfish.

The cave went way back inside, and stupid me, I forgot my flashlight. In retrospect, it was probably a good thing, because the tide was quickly rising and soon Sherrell was yelling for me to stop climbing around inside the cave and get out -- the tide had already risen almost a foot.

From Effingham Bay, we set sail for Bamfield, the town on the east side of the Sound. This is the last stop on the west coast for us, as after Bambfield the long slog down the Strait of Juan de Fuca leads us to Victoria, our last Canadian Port.

Bamfield was a quaint little town running down both sides of the inlet, where we took showers, did laundry and a little food shopping -- all the cruiser basics. Then, we headed back out into the Pacific. Before entering the Straits of Juan de Fuca, we had to travel East for about 15 miles, cross over the Swiftsure Bank, then we would be passing Neah Bay and the entrance to the Straits.

For weeks, we'd listened to the weather in the Straits. It was always blowing from the West, always. But the day we sailed around Cape Beale and headed eastward, it was blowing against us, from the East. Amazing! We had to motor for 10 hours before entering a large open cove called Port San Juan. Every Swiftsure race I've been in (all 3), we had strong westerlies.

We saw a lot of little sport fishing boats, and I mean LITTLE - we couldn't believe folks would take these little 10 - 15' boats out to the entrance of the Straits. But we also saw large commercial bottom draggers, which we still can't believe is legal. They drop a net in several hundred feet of water and scoop up everything and dump it on the deck of their boat, picking the creatures they want to keep and tossing the maimed and/or dead "by-catch" (animals they cannot sell) over the side. We went by one as he was pulling up his net, and I kept screaming to the fish, "SWIM DOWN! SWIM DOWN! EVERYBODY SWIM DOWN!" But I don't think they heard me, the bottom dragger pulled them all out of the water and dumped it on their deck. (If you don't get my reference, you have to see "Finding Nemo").

Despite all that, we made good time motoring and headed to a strange anchorage. Port San Juan looks like someone dipped their finger into an otherwise perfectly straight edged canyon wall lining the south of Vancouver Island for almost 100 miles. It is a large open bight that is barely out of the swell. (See the chart at the beginning of this story).

The choice is to either anchor here in this open roadstead, or keep going for another 10 hours or more, arriving in the dark. We chose to stop, even if it was bouncy.

We set a bow anchor, and lined the boat up so we faced into the swells and then dropped a second anchor off our stern. This kept us facing into the prevailing waves to make the night more comfortable.

The anchorage was rough, but the view was amazing. We looked straight out into the Straits and the very Northwestern edge of the United States, Cape Flattery. We'll have to get more used to anchorages like this for when we head to California and Mexico.

The next day, a westerly gale was predicted. Well, at least it's a westerly, we both said. We had over 50 nm to go and a stiff breeze would make the 11 hour day more enjoyable. As it turned out, we were able to sail a majority of the way and averaged over 5.5 knots (very fast for us considering adverse current for several hours).

The tides were really strong and for the first 3 hours we fought 2+ knots of current, then from there on out, it was like getting sucked down the Strait. We hit over 9 knots going through Race Passage. Anyone who has ever sailed in the Swiftsure race, or done any sailing out of Victoria, Canada will recognize the following light.

This is the famous Race Rocks about 10 nm outside of Victoria. It also symbolizes the end of our circumnavigation of Vancouver Island.

We arrived in Oak Bay in the late afternoon, anchored in a crowded anchorage and toasted our trip with some crappy tasting Canadian beer.

Our last trip through the PNW wilderness was fantastic. The sailing was usually good, but we still put about 150 hours on the engine--better than the 500 hours to Alaska and back. Our plan is to make some more modifications to the boat in the next couple of weeks, then make the passage south to San Francisco and beyond!

AFTERWORD:

Jezebel's thoughts on the whole matter were rather negative. If she were to give anyone advice about doing this trip, it would be, "Don't do it!" She did, however, come out of her shell tremendously. She's always been a frightened cat, but after facing the open ocean and the big waves, she found a new lease on life. She comes out of hiding while we are sailing and now she even explores outside the boat on her own. Two things she hasn't done in over a year of living on the boat.

She also found a few new places to hang out and watch the action from, like on top of our chart box under the companionway stairs.

Sarana anchored in Roche Harbor

Sarana anchored in Roche Harbor